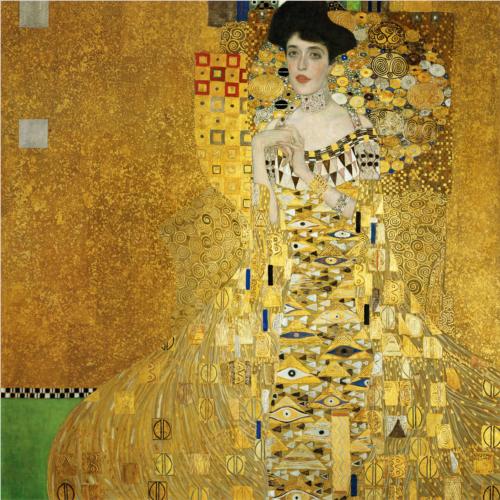

Hollywood is not known for accuracy when it comes to history, much less art history. However, “Woman in Gold,” a film dramatizing the real-life legal battle between Austria and Maria Altmann, an American Holocaust survivor, over a Gustav Klimt portrait depicting her aunt, hews remarkably closely to the facts:

• In 1998, the Austrian Parliament passed a resolution mandating that federal museums return Nazi-looted artworks that meet certain specified criteria. Though often referred to as a law, this resolution is in fact a set of extrajudicial guidelines. The 1998 resolution does not in any way change Austria’s existing laws, which grant clear title to good-faith purchasers of stolen art after three to six years.

• Austrian restitution claims are reviewed by a committee that meets behind closed doors, and the evidence supporting its decisions is never made public. The entire process can seem untenably subjective, regardless of the outcome.

• Austria’s high filing fees make it difficult for foreigners to appeal the restitution committee’s decisions. By prevailing in his arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court, Maria Altmann’s lawyer, Randol Schoenberg, established her right to sue in America. This prospect convinced Austria to accede to binding arbitration.

• Austria’s restitution guidelines provide no possibility of compromise or settlement. Only after the Austrians lost the arbitration proceeding were they amenable to negotiating with Altmann, and by then her position had understandably hardened.

Some Austrians will surely complain that “Woman in Gold” depicts them as unrepentant Nazis. In Austria’s defense, it must be said that the 1998 restitution resolution is virtually unique. Few nations have made similarly comprehensive attempts to deal with the legacy of Nazi art looting. Austria is also one of the only countries that have set aside considerable government funds for provenance research. The cost of such research has hampered restitution efforts elsewhere, including in the U.S.

The unfortunate fact is that Austria was not alone in failing to properly restitute Nazi looted art after World War II. The entire international art world largely ignored the issue for decades. Today, when most witnesses to Nazi theft have died, it can be impossible to determine the circumstances surrounding alleged instances of spoliation. Inevitably, present-day restitution efforts are going to fall short of what might have been achieved had the issue been systematically addressed immediately after the war.

Not all claimants are as successful as Maria Altmann, nor are all restitution claims as seemingly clear-cut. “Woman in Gold” may be accurate, but most such cases are far more complicated and nuanced than the film would lead us to believe.

(Images from top: Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie, NY; the late Maria Altmann sitting with her lawyer, Randol Schoenberg, alongside a movie still of actors Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds.)