The following originally appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Yale Medicine, the magazine of the Yale School of Medicine.

“People who didn’t live through this can’t appreciate how hopeless it was,” said Susan Wheeler, curator of prints and drawings at the Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, referring to the early stages of the HIV/AIDS crisis. “AIDS was a death sentence. Everybody knew people who had died or were dying.”

People suffering and dying from HIV/AIDS is the subject of “ ‘The AIDS Suite,’ HIV-Positive Women in Prison and Other Works,” an exhibit of drawings that ran at the library from September through January 10. The drawings are the work of Sue Coe, an activist/artist who is represented in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art. Coe spent time with patients at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston in 1994, and with infected inmates at a women’s prison in nearby Texas City in 2006. The inmates served as “peer group educators,” supporting new arrivals who were also afflicted.

Coe began the Galveston project, which was initiated by The Institute for the Medical Humanities, when fellow artist and psychiatrist Eric Avery, M.D., invited her to visit the medical center’s AIDS ward. “Drawing allowed me to spend time with patients, and they could see me draw and tell me of their lives,” Coe wrote.

The purpose of the hospital project, Wheeler said, was to focus less on the patients than on the staff. “The safety measures were not in place at the time, so people were putting themselves at risk,” she said, pointing out that AIDS was then the major cause of death for Americans between ages 25 and 44. “And all staff members were volunteers.”

Two poster-size drawings in the exhibit include long paragraphs of text hand-written by the artist.

One of them, Dr. Pollard Leads Ethics Rounds, depicts Crystal, a 22-year-old white sex worker with late-stage HIV. The text reveals the debate among caregivers over whether to give her a morphine IV. Because she had refused treatment two weeks previously when she had been competent, her caregivers decided “to rehydrate the patient and send her home,” even though Crystal’s mother wanted further treatment. A psychiatrist at the bedside noted, “It is hard for doctors to let their patients die.”

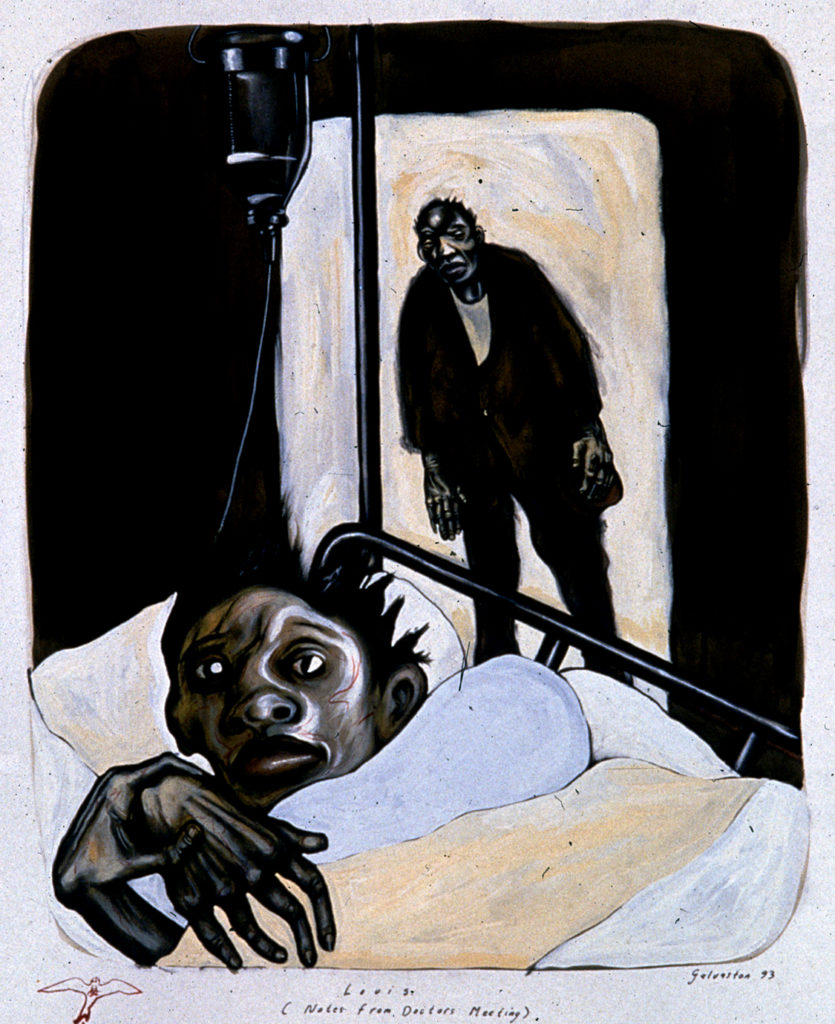

The other work that includes a narrative is Louis. (Notes from Doctors Meeting). Shown wild-eyed and tied to his bed, he is described as black, gay, 35 years of age, with late-stage AIDS. He is incoherent, with renal insufficiency, and has had AIDS for between four and five years. His father has arrived, but Louis doesn’t recognize him. The doctors want to send Louis to hospice, but his family is not cooperating: “Family denies he is gay and has AIDS. They want more aggressive treatment for cancer.”

As Wheeler put it, “People didn’t accept that their kids were gay.”

The large drawings first appeared in The Village Voice and were acquired by the library in 2015.

Wheeler said she hoped that the works—which can be seen by request after the exhibit closes—will be used in teaching. Everyone she has shown through the exhibit has been visibly affected, she said.

Among them is Anna Reisman, M.D., associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Program for Humanities in Medicine. The images remind her of the patients she cared for during her training at New York’s Bellevue Hospital Center in the mid-1990s, Reisman said, “when it seemed like every single hospital patient was a young person dying of AIDS.”

Seeing the drawings for the first time, Reisman said, “I remember being on the verge of tears. I’ve always found it difficult to describe to students and trainees what it was like to work in the midst of the epidemic. Sue Coe’s drawings say it all, and more.”