“Few artists are as universally loved as Käthe Kollwitz” — Elizabeth Prelinger, National Gallery of Art

“Few artists are as universally loved as Käthe Kollwitz” — Elizabeth Prelinger, National Gallery of Art

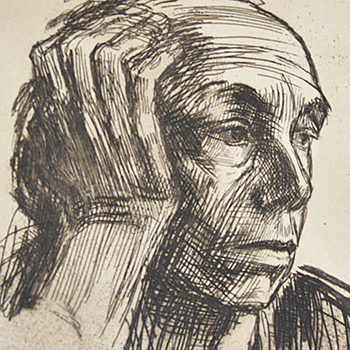

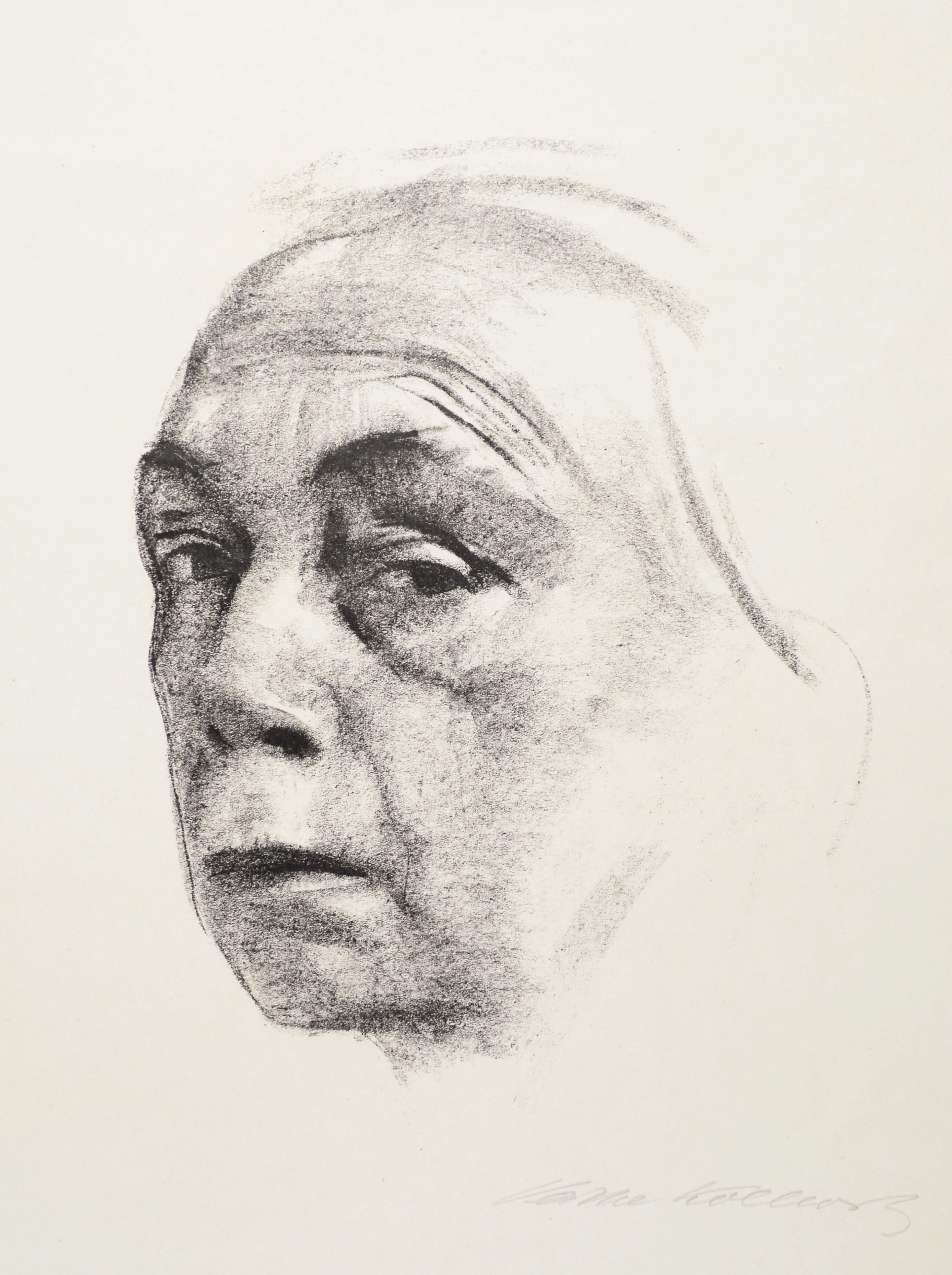

Like other successful women artists of her generation, Käthe Kollwitz was an outlier. Her extraordinary career, which spanned over half a century, was made possible by the fortuitous convergence of three trends: the revival of printmaking as a significant art form in Germany; the incipient emancipation of women; and growing support for a more egalitarian social order. Her oeuvre comprises 99 etchings, 133 lithographs, 42 woodcuts, 19 extant sculptures and roughly 1,450 drawings, among them some of the most indelible images to come out of Germany between the two world wars.

Born Käthe Ida Schmidt in Königsberg, eastern Germany, to a middle-class family with strong socialist leanings, Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) had a liberal-minded father who encouraged her talent. Between 1881 and 1889, her artistic training included private lessons with a copper engraver and study at the Berlin and Munich Schools for Women Artists. In 1891, two years after leaving the Munich school, she married Karl Kollwitz (a physician who shared her political beliefs). The pair relocated to Berlin, where Dr. Kollwitz’s patients were principally the very poor.

Kollwitz’s “politicization,” as she termed it, stemmed from “faith.” She depicted workers because she empathized with them and found them beautiful. Time and again she represented iniquity in an effort to call her viewers to action. By the start of World War I, she had received widespread acclaim for her print cycles Revolt of the Weavers (1893-98) and Peasant War (1902-08), both of which traced narratives of rebellion and repression. The artist was also involved with various social, political and artistic organizations, among them the Berlin Secession and Simplicissimus, a satirical magazine.

In October 1914, the youngest of Kollwitz’s two sons, Peter, was killed at the Russian front only months after enlisting. His death fueled the increasingly pacifist tone of the artist’s work, and she henceforth dedicated her efforts to her late son’s memory and to the protection of young lives. Her woodcut cycle War (1921-22) was a shattering indictment of human conflict. Kollwitz was appointed as the first female professor and member of the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts in 1919. In 1928, she became the director of the master studio for graphic arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin. Throughout these years, she also worked on a memorial to Peter, a sculpture of two mourning parents, which in 1932 was placed in the military cemetery in Belgium.

Although Kollwitz was not harassed by the National Socialist Party as much as some other artists, she was forced to resign from the Academy of Fine Arts, in part as a result of signing an “Urgent Appeal” to unite socialist and communist leaders against fascism. Forbidden to exhibit, she worked quietly on her final print cycle, Death (1934-37) and on sculptures, many of which could not be cast until after her death. Kollwitz died in 1945, shortly before the signing of the armistice.