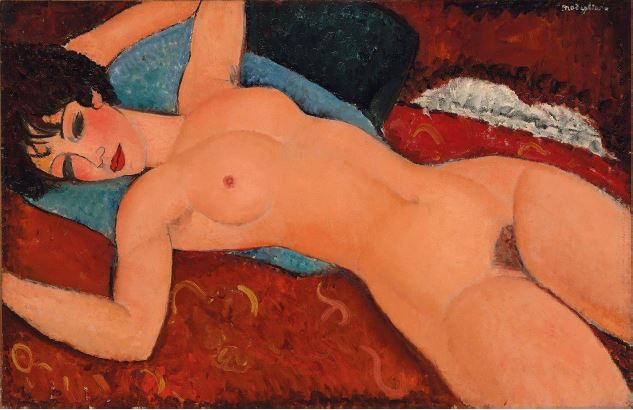

Amadeo Modigliani became the latest man to join the nine-figure club when his Reclining Nude sold for $170.4 million at Christie’s on November 9, 2015. Why are all the most expensive artists male?

It has been nearly 45 years since art historian Linda Nochlin asked the rhetorical question, “Why have there been no great women artists?” In the intervening period, the domestic demands and societal restrictions that once prevented women from fully developing their talents have greatly diminished, both within and beyond the art world. Female students often outnumber men in university art and art history departments. However, despite the proliferation of female artists, gallerists, curators and critics, a glass ceiling still limits access to the highest professional levels. Even as modern art history is gradually being rewritten to give more attention to once-excluded minorities (not just women, but African Americans, Native Americans and sundry “outsiders”), the market continues to favor white males like Picasso, Warhol, Pollock, Rothko and Bacon.

Amadeo Modigliani became the latest man to join the nine-figure club when his Reclining Nude sold for $170.4 million at Christie’s on November 9, 2015. Of course the painting was bought by a man. Only men earn the billions required to pay such prices. Nonetheless, while the upper reaches of the art market may be the exclusive domain of male collectors, this fact alone does not explain why today’s most expensive artists are all male.

There were, in fact, many great women artists in the twentieth century. The reason they have not attained the “trophy” status of their male peers is not owing to the quality of their work, but to the male-dominated narrative that still colors our view of modern art history. A case in point is Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), the subject of the Galerie St. Etienne’s current exhibition. Modersohn-Becker overcame the obstacles that beset women artists in the early 20th century, and in seven years of concentrated effort produced a body of work that ranks among the greatest achievements of early modernism. In many respects she was ahead of her time, bringing modernism to Germany in advance of the men associated with the Brücke and Blauer Reiter groups.

But our understanding of German modernism remains centered on those male Expressionists. Like many female artists, Modersohn-Becker does not fit comfortably into the sequence of avant-garde “isms” that punctuate twentieth-century art history. Instead, she followed her own path, picking her way through influences that ranged from ancient Egyptian mummy portraits to the cutting-edge innovations of Cézanne and Gauguin. Although deeply impressed by the colors and forms of the Post-Impressionists, Modersohn-Becker never abandoned her underlying fidelity to nature. She eschewed both the abstractionist tendencies of the French and the bold urgency characteristic of the German Expressionists. Her goal was to capture the primordial, unchanging essence of her subjects, the “inner vibration of things.”

Difficult to classify, Paula Modersohn-Becker lacks the name-brand recognition of the top-ranking male modernists. In a trophy-obsessed art market, collectors pay the highest prices for well-known names: names that will impress their friends and that they (perhaps mistakenly) imagine will sustain the value of their investment. However, we are living through a period of art-historical revisionism, and standards can change very quickly. Ultimately, quality prevails.