Koloman Moser (1868 Vienna – 1918 Vienna) earned the nickname “Tausendkünstler” (thousand-artist) because of the many facets of his work: graphic art; design of objects, furniture, and interiors; and architectural and theatrical design. He was, in addition, a painter, a teacher, and a central figure in the most important artistic events to take place during the cultural flowering of turn-of-the-century Vienna.

Moser’s father was a steward at a school that included crafts training in its program, and he was an observer of this from an early age. After beginning his studies with applied arts and drawing, Moser was accepted at the Akademie der bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts) in Vienna and later moved to the more progressive Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts). After his father’s death in 1888, Moser began working as a graphic artist to support himself, contributing illustrations to popular magazines and books.

In 1895, Moser was a founding member of the Siebener Club (Club of Seven), a group of forward-looking artists and architects, including Joseph Hoffmann and Joseph Maria Olbrich. In 1897, Moser, along with Hoffmann, Olbrich, and Gustav Klimt, among others in Vienna’s avant-garde, was a founding member of the Vienna Secession, the multi-disciplinary group of artists that broke away from what they saw as the conservative Vienna Academy and its historicist style, to create new, modern art. This modernity, they believed, could and should be seen in daily life—in architecture and interior design, furnishings and objects—just as much as in paintings.

Moser was a significant contributor to the Secession’s journal, Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring), and designed Secession exhibition posters. For the Secession building (Joseph Maria Olbrich, 1897), Moser contributed designs for the exterior and interior, as well as for the large circular stained glass window in the building’s entrance. He was also active in exhibition design, organizing a major exhibition of Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler’s work, seen at the Secession in 1904. Additionally, Moser always remained busy with graphic design projects and the design of textiles, furniture, glassware, and china, which were produced by prominent manufacturing firms. Moser’s simplified, stylized designs, with their masterful use of positive and negative space or multiple picture planes, were well-known and admired. In 1900, Moser was made professor of drawing and painting at the Kunstgewerbeschule, joining Hoffmann and other like-minded colleagues. There, Moser encouraged his students to work in both the fine and decorative arts, and he remained an influential teacher at the school until the end of his life.

In 1903, Moser, Hoffmann, and financier Fritz Wärndorfer founded the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop) the art and design collective that would be the source of much of the most inventive and influential work created during this period. The Werkstätte took as its ideal the “Gesamtkunstwerk” (total artwork)—a unification of artists and craftsmen of different disciplines (painting, sculpture, architecture, design, etc.) in the creation of an overarching lifestyle concept. Beyond its conceptual foundation, the Werksätte had the important function of being an entity through which the work of its collaborators could be fabricated, exhibited, commissioned and sold.

In the work program of the Wiener Werkstätte, published in 1905, Moser and Hoffmann stated:

“We wish to establish intimate contact between public, designer and craftsman, and to produce good, simple domestic requisites. We start from the purpose in hand, usefulness is our first requirement, and our strength has to lie in good proportions and materials well handled . . . The work of the art craftsman is to be measured by the same yardstick as that of the painter and the sculptor . . . So long as our cities, our houses, our rooms, our furniture, our effects, our clothes and our jewelry, so long as our language and feelings fail to reflect the spirit of our times in a plain, simple and beautiful way, we shall be infinitely behind our ancestors.”

Moser and Hoffmann closely collaborated on the design of much of the Werkstätte’s early production, with its trademark geometric simplicity (so much so that it is sometimes difficult to discern the work of one from the other). The Werkstätte’s creations eventually included graphic arts, furniture, ceramics and glass, silver, fashion and textiles, bookbinding, and toys, in addition to architectural and interior design projects. There were Werkstätte stores in Vienna, Berlin, and, later, New York, and the Werkstätte would remain active in various forms for close to 30 years, until 1932.

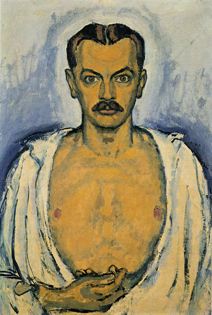

In 1905, Moser married Editha Mautner-Markhof, who was from a very wealthy family. The following year, when the Werkstätte was in need of additional funding, she was approached for a loan. This precipitated a disagreement between Moser and the Werkstätte, which eventually led to his resignation in 1907. After leaving the Werkstätte, Moser continued his design work, including the creation of postage stamps commemorating the Emperor Franz Joseph’s 60th jubilee and, later, 100 kronen banknotes. His interior design projects included contributions to the exhibition design of the Vienna “Kunstschau” (“Art Show”) in 1908 and 1909 and stage design for the 1910 premier of Julius Bittner’s opera Der Musikant (The Musician) at the Vienna Hofoper (Court Opera). Moser also devoted increasingly more time to painting. In 1911, Vienna’s Galerie Miethke held the first and only one-man show of Moser’s paintings during his lifetime. Moser died of cancer in 1918, at the age of 50.

Throughout his career, Moser’s work was widely seen and appreciated, in Vienna and internationally, in exhibitions, special publications, and magazines such as Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration (German Art and Decoration) and England’s The Studio. Moser’s work is the very definition of Viennese turn-of-the-century design, and, though his name is less well known than that of his colleague Hoffmann, his influence has been felt throughout modern design.