Pavel Leonov was born in 1920 in Orel, a town south of Moscow, not far from the Ukrainian border. He left his family at age 16 to escape his father, a man he described as a “professional alcoholic.” A few years later, Leonov served in the military, hoping to rise through the ranks, only to clash with his superiors and even some of his subordinates. This led to his initial confinement in a prison camp in Georgia. Although Leonov was released after a few years of service, he found himself in and out of labor and prison camps until 1955, two years after the death of Stalin. Over the course of his confinement, Leonov learned a variety of trades, including woodcutting, ship repair, road-building, sign painting, farming and metal work. Leonov’s first attempts at painting came while in the army, when he started drawing portraits of his fellow soldiers. Unfortunately, none of these works survive. Later, while working in a tractor factory, the ever-ambitious Leonov taught himself to draw from a manual. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Leonov attended the People’s Free University in Moscow, where he was influenced by the significant underground artist Mikhail Roginsky. Soon after, Leonov’s works appeared in several Soviet exhibitions of amateur art in Moscow. In 1988, Leonov’s works were exhibited in Paris and Laval, France. From the 1980s until his 2011 death in the village of Mekhovitsky, Leonov made his home in remote country settings.

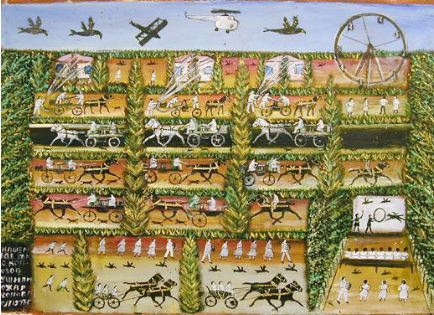

Leonov termed his paintings “inventions.” They are large, colorful works painted on unstretched, roughly-cut canvases depicting idealized scenes of nature and town life. The images within these paintings, neatly compartmentalized into sections the artist called “rooms” or “television sets,” reflect his obsession with order. By combining images of historical events (scenes of famous battles) and Russian cultural icons (the poets Pushkin and Esenin) with more contemporary landscapes, and embellishing the remote landscape he inhabited with scenes from his travels or literary sources, Leonov collapsed time in his paintings. The artist’s lived reality was transformed into a peaceful, tidy fantasy world. Animals dance as birds and helicopters fly overhead; an audience visits Leonov’s studio and commends him for his beautiful paintings, while a group of peasants listens to a famous poet. Though Leonov’s fellow villagers might have poked fun at such “fanciful” stories, these pictures afforded their author a chance to pursue his dreams, while remaining universal enough to allow others to join in his fantasies.

—

While Leonov gained some recognition in his homeland and in Europe, the Galerie St. Etienne was the first American gallery to feature his work.