Otto Mueller was born on October 16, 1874, in Liebau, Silesia (now Poland), in the Sudeten mountains. Young Otto spent his early years with his mother, brothers and sisters at his grandparents’ Liebau estate, but later moved to join his father in Görlitz, where he attended primary and secondary school. Unhappy with these traditional studies, Mueller apprenticed to a lithographer at the age of sixteen. Here began his life-long love of printmaking, and lithography in particular. Recognizing his son’s artistic talent, Mueller’s father agreed to allow him to enroll at the Academy of Art in Dresden, where he studied from 1894 to ’96. Thereafter, he tried to attend the Munich Academy, but was refused admission to Franz von Stuck’s class. Preferring to educate himself, Mueller moved to Wolfratshausen, south of Munich, and made his way to Dresden in the fall of 1899.

Although Mueller worked in Dresden and the surrounding region until 1908, he did not meet any of the artists affiliated with Die Brücke, the artists’ community founded by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, E.L. Kirchner, Erich Heckel, and Fritz Bleyl, until his move to Berlin later that year. It was here that Mueller met and befriended Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Rainer Maria Rilke and Heckel. A turning point in Mueller’s career came two years later, in 1910. After his work was rejected by the Berlin Secession, he joined Emil Nolde, Hermann Max Pechstein, and other members of Die Brücke in an alternative exhibition, Rejects of the Berlin Secession, under the auspices of a new group, the Neue Sezession. Here, Mueller’s work won the admiration of the Brücke artists, who invited him to join the group. Mueller shared with his Brücke colleagues a feeling for uncorrupted nature, which led him to accompany Heckel and Kirchner to the Baltic coast and to the Moritzburger Lakes near Dresden. Mueller remained affiliated with the group until its dissolution in 1913, and also exhibited with the artists of the Munich-based Blauer Reiter group.

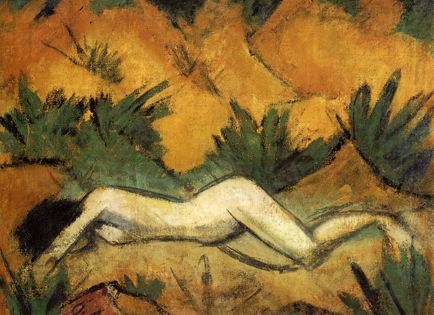

Mueller’s early works were inspired by Post-Impressionism, Jugendstil and Symbolism. However, after his move to Berlin in 1908, his style became more and more Expressionistic. Mueller’s artistry focused less on the primitive, passionate emotion explored by his contemporaries than on the harmonious simplification of form, color and contour. He is best known for his female nudes in various landscapes, which today are considered some of the best nude compositions of the period. Mueller’s clean, angular emphasis on the silhouette, classically elegant, and graceful appearance of his figures define his best work.

After the break-up of Die Brücke, Mueller maintained contact with the former members of the group. He traveled to Fehmarn with Kirchner in the summer of 1913 and continued his friendship with Heckel. Mueller served in the German army for one year during World War I and was hospitalized briefly in 1917. His imagery seems not to have been affected by these wartime experiences; these post-war works differ little from that made before the war.

In 1919, Mueller began teaching at the Breslau Academy and continued there until his death in 1930. Ever the journeyman, he traveled extensively in Eastern Europe during the 1920s, and his art of the period reflects his fascination with the region’s gypsy culture. True to his early aspirations, Mueller’s interest in printmaking lay primarily in lithography. Of his total oeuvre of 172 prints, only six were woodcuts, and one was an etching.

Like many fellow Expressionists, Mueller was branded a Degenerate artist by the Nazis. In 1937, 357 of his works were removed from German museums.