Karl Schmidt-Rottluff was born Karl Schmidt in the town of Rottluff on December 1, 1884. Schmidt met his lifelong friend and fellow founding member of Die Brücke, Erich Heckel, at high school in Chemnitz in 1902. Both Heckel’s and Schmidt’s artistic and philosophical interests led them to join “Vulkan,” their school’s debating society. The lively anti-bourgeois art and literary theory discussions manufactured by the group created a stimulating forum for both teenagers. Nietzsche was discussed with special interest, perhaps leading to Die Brücke’s later emphasis on the philosopher and his writings.

Following Heckel’s lead, in 1905, Schmidt enrolled as an architecture student in the Sächsische Technische Hochschule in Dresden. That same year, looking to distinguish himself from the other commonly-named Schmidts, Karl hyphenated his name to include Rottluff, an homage to his home town. Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, the artist, was born. Through Heckel, who had enrolled in the academy the previous year, Schmidt-Rottluff met Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Fritz Bleyl. Together, the group formed Die Brücke. Schmidt-Rottluff devised the name for the group after a quote from Nietsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end.” Something of a loner, Schmidt-Rottluff was less of an active participant in the group than Heckel and Kirchner, but he remained committed to the group’s ideals, and in 1906, he even suggested that Emil Nolde, a fellow loner with whom Schmidt-Rottluff had become close, join them. Rosa Schapire, an art historian from Hamburg (who would later publish the catalogue raisonné of Schmidt-Rottluff’s graphic works pre- 1923), became the group’s most important patron. The Hamburg lawyer Gustav Schiefler (who later wrote the catalogue raisonné of Nolde’s graphic works) also began collecting Schmidt-Rottluff’s prints.

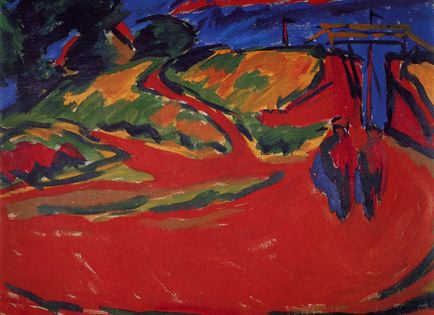

The following year, Schmidt-Rottluff abandoned school in order to concentrate exclusively on making art. Upon devoting himself to painting, Schmidt-Rottluff began to spend more time alone in the tranquil coastal region of Dangast, painting the remote scenery of the North Sea, which provided a wealth of motifs for his landscape paintings. From 1907-12, Schmidt-Rottluff spent part of each year in or near Dangast. Occasionally, Heckel would accompany him, but primarily he made these trips alone. He also developed his talents as a printmaker, and as early as 1909, was instrumental in reviving woodcut as a medium perfectly suited to Die Brücke’s expressive impulses. Of all the Die Brücke artists, Schmidt-Rottluff was the most extreme in simplifying form and exploiting the medium for its unique pictorial abilities. Using the grain of the wood as a graphic device, both Schmidt-Rottluff and Nolde influenced each other, pioneering revolutionary techniques in emphasizing print surfaces. Between 1906 and 1912, Schmidt-Rottluff took great pride in pulling his own prints, which he produced in small editions; after 1912, he left the task to professionals and produced larger editions of 25-30, with some editions extending to 100.

When Schmidt-Rottluff followed the other members of Die Brücke to Berlin in 1911, he came into contact with Cubism, Futurism, and African tribal art, all of which influenced his style greatly thereafter. He developed an increasingly reductive geometric formal language that placed a greater emphasis on draughtsmanship; Schmidt-Rottluff now emphasized firm, clear outlines filled in with subdued color, replacing the glowing, brightly colored shapes of his former work. The artist had his first one-man show at the Galerie Commeter in Hamburg in 1911, followed by participation in the Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne. A substantial number of paintings, watercolors and graphic works were produced during this fertile time. After Die Brücke disbanded in 1913, Schmidt-Rottluff continued to streamline his pictorial conceits, continuing the stylistic trend that began with his move to Berlin. His woodcuts of 1914 are the epitome of this achievement, revealing a monumental and stylized artistic vocabulary that Schmidt-Rottluff would rely on for the remainder of his graphic output.

In 1915, Schmidt-Rottluff was drafted for military service in Russia and Lithuania. Rather than exploit his military experiences for graphic subject matter, Schmidt-Rottluff preferred to reflect only indirectly on the horrors of war. During his service, he produced only woodcuts and wooden sculptures, most notably a cycle of nine woodcuts based on the life of Christ, widely considered to be his graphic masterpiece.

In 1918, at war’s end, Schmidt-Rottluff returned to Berlin and married Emy Frisch. Though apolitical, he became a member of Arbeitsrat für Kunst in Berlin, a short-lived socialist-style union of radical Berlin architects, painters, sculptors and art critics. He continued working in all media, but gradually lost interest in graphics, and by 1927, ceased working in this medium altogether. In 1931, he became a member of the Prussian Academy, only to be expelled from his post in 1933. In 1937, the Nazis deemed Schmidt-Rottluff’s work “degenerate,” and he was prohibited from exhibiting and painting in 1937 and 1941, respectively. After his studio was bombed in 1943, Schmidt-Rottluff chose to live in exile in Rumbke at the Leba Lake in Pomerania.

The artist's reputation was gradually rehabilitated after the war. He later returned to Rottluff, where he lived until 1947, when he was asked to become, like Hermann Max Pechstein before him, a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in West Berlin, and went on to receive numerous honors and exhibitions later in his life. An endowment created by him and his wife in 1964 provided the basis for the Brücke-Museum in West Berlin, which opened in 1967 as a repository of works by members of the group. In 1975, shortly before his death, Schmidt-Rottluff bequeathed money to his foundation to support a program that continues today: a €35,000 stipend awarded bi-anually to three or four emerging artists. Karl Schmidt-Rottluff died at the age of 92 on 10 August, 1976.

A prolific printmaker, the artist produced 300 woodcuts, 105 lithographs, 70 etchings and 78 commercial prints described in the Rosa Schapire catalogue raisonné.