George Grosz spent his early life moving with his mother between his birthplace of Berlin and Stolp. He began private drawing lessons in 1901, the year after his father’s death, and in 1908, he entered the Royal Academy in Dresden, from which he graduated with honors. He volunteered for the army in 1914, and after a year at the front, suffered a nervous breakdown. He considered this a physical and psychological revolt against military violence. Drafted back into the army in 1917, he avoided active service and instead passed the time in a sanitarium.

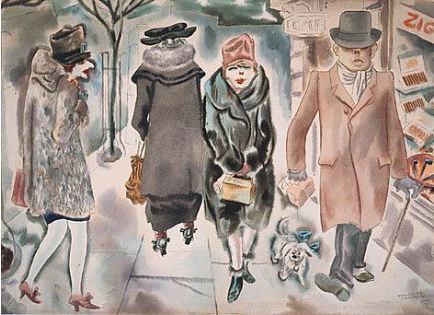

Around the time of the 1918 November Revolution, Grosz focused his pictorial attack on what he later termed “The Pillars of Society”: the military, the clergy, and above all, the bourgeoisie. He was concurrently engaged with the Dada movement, the German Communist Party (KPD) and the Internationale Arbeiterhilfe, which brought him into contact with fellow members Otto Dix and Käthe Kollwitz. Grosz’s innate, generalized mistrust of ideology limited his activity within the KPD, but he remained loyal to the party for several years. He severed his ties with them when asked to create propaganda posters. This break coincided with a 1922 visit to Moscow, where he was disillusioned by the city’s numerous social woes. Grosz nevertheless remained a committed socialist, and in 1924, he became a leader of the leftwing Rote Gruppe.

In due course, Grosz’s satirical attacks on corrupt capitalist society invited legal trouble. His portfolio God on Our Side was confiscated in 1920, and he was arrested and fined for maligning the military. Two years later he was fined again, this time for defaming public morals in the portfolio Ecce Homo. Grosz was possessed of an acute, prescient awareness of the threat posed by the Nazi Party. As early as 1925, he began ridiculing Adolf Hitler and issuing increasingly strong warnings about Nazism. By the end of the 1920s, the political climate in Germany had swung right, and Grosz was imperiled. He accepted a teaching position in the United States in 1933, as the Nazi party was voted into power. Though the artist and his family had physically escaped danger, Grosz’s art remained under scrutiny. Several of his works hung in the Nazi-sponsored 1937 exhibition “Degenerate Art.” In the U.S., however, Grosz became less political, and benign cityscapes, landscapes and nudes came to predominate in his work.

Grosz returned to Germany in 1958, and died in Berlin in 1959.