Franz Marc was born in Munich on February 8, 1880. A serious, intellectually and religiously inclined child, Franz was clearly influenced by his mother, Sophie, a strict Calvinist of Alsatian origin. Franz and his older brother Paul grew up in a middle-class household that was notable for its artistic leanings. Sophie Marc’s brand of “Christian Socialism,” with its emphasis on humility, modesty, spiritual values, literature, philosophy and liberal Christian ideals, informed her children’s education and ambitions. There was little direct pressure placed on the boys, and both Paul and Franz ambled through their early adult years, veering from one professional path to another until each discovered a suitable career. After briefly considering the priesthood, Franz enrolled at Munich University to pursue philology or to become a secondary school teacher. Only later did he decide to followed in the footsteps of his father, Wilhelm Marc, a modestly successful professional landscape painter. After leaving school to perform his year of compulsory military service, Marc decided to become a painter. In 1899, he enrolled at the Munich Academy of Art, where he studied for two years.

Marc very much admired the German Romantic painters, and his early works’ academic tendencies reflect the influence of Runge, Friedrich, Kobell, Blechen, Rethel and Schwind. Marc’s professors at the Munich Academy of Art, Gabriel Hackl and William von Diez, stressed the importance of plein-air painting and restrained naturalism. Very few of Marc’s works from this early period survive, but those that do are very characteristic of the Munich School. Unhappy with his artistic education, Marc decided to end his studies in October of 1902 in order to pursue his own relationship with nature. He traveled to the Alpine foothills of Bavaria and later accompanied fellow student Friedrich Lauer to Paris, Brittany and Normandy. While he was greatly moved and excited by the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, whose work he now witnessed firsthand, their style had little visible impact on his own.

Marc’s personal and artistic life was next turned upside down by a torrid love affair with Annette von Eckardt, a married mother of two. Von Eckardt was a well-known art and antiques dealer in Schwabing, an intellectuals’ and artists’ enclave in Munich where Marc rented a small studio. Since Marc had not yet found a way to make a living from his art, he followed Von Eckardt into the art business. She helped him along and found him small commissions, such as designing publications and executing portraits for friends and acquaintances. Through this work, Marc developed relationships with the dealers Emil Hirsch and Heinrich von Pohoretzky, who would prove useful later on in his artistic career. Marc and Von Eckardt, an artist in her own right, even collaborated on a few projects. These works reflect the couple’s shared interest in non-European art, with an emphasis on Eastern literature, including Indian Vedas, Chinese love poetry and Arabic verse. Marc was also influenced by Byzantine studies and no doubt consulted the periodical Byzantineische Zeitschrift, which his brother Paul edited until World War I. Munich Art Nouveau was another strong influence, for Marc as well as his contemporaries.

Marc and Von Eckardt separated at the end of 1904, and though they remained on good terms, Marc was quite devastated at the relationship's end. Around this time, he became inspired by the Scholle artists, a group founded in 1899 whose loose, quick, broad-brushed style resembled a crude Impressionism that one of the members dubbed “Improvisationism.” Marc followed the Scholle artists’ exhibitions at Kunsthandlung Brackl, and attempted (unsuccessfully) to contribute to Jugend, a magazine closely associated with the Scholle group. In early 1905, Marc met Maria Franck, an artist from Berlin studying at the Künstlerinnenverein, who would later become his wife. However, still suffering from his break-up with von Eckardt, Marc was not able to fully commit himself to Franck. To escape from his depression, he traveled to Salonika and Mount Athos with his brother in 1906. Returning to Germany, Marc continued his relationship with Franck, but also began a second relationship with Marie Schnür, a comely instructor at the Künstlerinnenverein. The threesome spent an emotionally charged summer in Kochel. To Franck’s dismay, on March 27, 1907, the artist married Marie Schnür, supposedly to help her raise an illegitimate son from another liaison. The night of their marriage, he left, by himself, for France. Once in Paris, Marc intensely studied the works of Gauguin, Van Gogh and the Cubists.

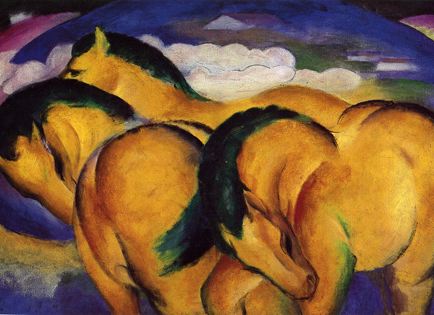

Although Marc was beginning to develop a sense of himself as an artist, he was a perfectionist who rarely felt satisfied. He often destroyed his early paintings, some of which had taken many months to complete. Still grasping for a definitive artistic style, Marc was influenced by his wife, whose work had been accepted in Jugend. During his marriage, he continued a correspondence with the jilted Maria Franck, and it is clear from these letters that he loved her and greatly respected her artistic opinions. Finally, after a visit to his wife’s family in Swinemünde, Marc realized his error. By the following summer he had rekindled his relationship with Franck, and together they moved to Staffelalm. From 1908, Marc felt a renewed sense of artistic vigor, and he and Franck painted together en plein-air, enthusiastically capturing the surrounding forest and the bright summer sunshine. He also began working on a life-sized painting of four horses, a turning point in his artistic development. Frustrated, Marc ended up destroying this work (which was later reconstructed), as well as two subsequent versions of the subject, executed in 1909 and 1910. These life-sized paintings (highly unusual in their scale for the time) were notable both for their attempt to break free from traditional easel painting and for their focus on animal imagery, which would become Marc’s hallmark. Aiming to recreate the animals “from the inside,” Marc made himself so complete a master of their anatomy that he felt qualified to teach classes on the subject, though in the end there were few takers. This anatomical knowledge gave him the ability to improvise. From this point on, Marc did not aim to merely copy nature, but to capture the spirit of nature and of “animal life.” Thus began his foray into Expressionism, as his works freed themselves from reality, and under the influence of his colleagues, moved ever closer to abstraction.

Marc had his first solo show in 1910 at Kunsthandlung Brackl in Munich. Impressed by the exhibition, the artist August Macke raced to Marc’s studio. Macke and Marc took an instant liking to one another and soon developed an intense friendship and artistic relationship. While Marc had made significant progress working out problems of form and composition, he had yet to develop as refined an approach to color. For his part, Macke, though quite young, was an amazing colorist. He had successfully absorbed the lessons of Matisse and Cezanne and generously passed these on to Marc. Thrilled to be working in a collaborative environment (which he’d until then experienced only with his girlfriends), Marc thrived. His solo show also brought him into contact with the publisher Reinhold Piper and the collector Bernhard Koehler, Sr., who would later become a patron of the Blaue Reiter. Koehler sent Marc fixed monthly payments in exchange for artworks. Marc’s constant worries about money were over. He gave up his Munich apartment and moved to Sindelsdorf. Though he continued to depict animals, he also painted female nudes, which comprise almost half his oeuvre until 1910.

In the fall of 1910, Marc saw the second exhibition of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM) at the Galerie Thannhauser. Founded the previous year, the NKVM included the artists Wassily Kandinsky, Alexei Jawlensky, Gabriele Münter, Marianne von Werefkin, Adolf Erbslöh, Alexander Kanoldt and Vladimir von Bekhteyev. After the Munich press savaged the exhibition, Marc wrote a positive review and was thereafter brought into the group’s fold. While he enjoyed the group’s artistic salons, he felt a particular kinship to Kandinsky. By early 1911, Marc was named chairman of the group.

A few months later, in May 1911, Marc received a letter from Kandinsky proposing an “almanac” that would showcase the work of cutting-edge painters, writers and musicians at home and abroad. Marc’s reply was enthusiastic, and his connections to Koehler (who served as patron) and Piper (who served as publisher) proved crucial to getting the project off the ground. Unfortunately, by the time the Blaue Reiter Almanac was published, in May 1912, the NKVM had disbanded. Kandinsky had been excluded from the NKVM’s November 1911 exhibition, and consequently the more radical members, including Marc, quit in protest. The first exhibition of this break-away faction, now known as “Der Blaue Reiter,” took place in December 1911 at the Galerie Thannhauser in Munich. In addition to Kandinsky, Macke and Marc, it included works by Albert Bloch, David and Vladimir Burliuk, Heinrich Campendonk, Robert Delaunay, Elizabeth Epstein, Eugen von Kahler, Gabriele Münter, Jean-Boé Niestlé, Arnold Schoenberg and Henri Rousseau. Unlike the North German Brücke group, Der Blaue Reiter did not put forth a consistent style; it was a more informal association. Drawn together by a mutual admiration for avant-garde art and philosophy, the Blaue Reiter artists’ work reflected their engagement with the key artistic movements of the time. While the members constantly fed off one another, each artist retained his or her own distinctive style.

Following the Blaue Reiter’s first exhibition, Marc set off to Berlin to spend time with his wife’s family. Turning the trip into a working holiday, he made contact with the Brücke artists Emil Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel and Hermann Max Pechstein. He selected a number of their prints for a planned second exhibition that would exclusively feature works on paper. Ever the hard worker, Marc organized all further activities of the Blaue Reiter, including traveling exhibitions and participation in group shows across the country. One of Marc’s last collaborative projects was an attempt, in the spring of 1913, to produce an illustrated edition of the Bible with contributions from Kandinsky, Alfred Kubin, Heckel, Oskar Kokoschka and Paul Klee.

Between 1912 and 1914, Marc absorbed the influences of Cubism and Futurism, which he distilled from careful study of artists such as Picasso, Braque and Delaunay. But Marc was no mere imitator of styles. While admiring contemporary art, he was careful not to lose the lessons of the past, and he continued to be influenced by the Romantic German painters he had first been drawn to during his days at the Academy. Marc also utilized, to great effect, the succinct color theories he had developed and refined through his collaborations with Macke and Kandinsky. His continued interest in spirituality and philosophy, combined with a constant striving to work problems through to their end, led Marc to create an entirely new pictorial vocabulary. These last years before World War I saw a marked increase in Marc’s focus on animals and nature drawing. His goal: to “put ourselves into the soul of the animal in order to guess the images they see. ” He endeavored to create an art seen through the world (Weltdurchschauung), rather than an art that merely looks at the world (Weltanschauung).

When war broke out in August 1914, Marc immediately enlisted. He was deeply troubled by Macke’s death in action shortly thereafter. Tragically, less than two years later, in 1916, Marc himself was killed in action in Verdun, France.

The Franz Marc Museum was founded in 1986 in Kochel Am See, a quiet Bavarian town south of Munich where Marc spent many fond summers as a child and as an adult.