Just as Henri Rousseau established the paradigm of the “naïve” artist for generations to come, the Swiss artist Adolf Wölfli must be considered among the first and greatest exemplars of “art brut.” Born in 1864 to an impoverished family of alcoholics and petty criminals, Wölfli was orphaned at the age of eight. He nonetheless managed to finish secondary school while earning his keep as a farmhand. In 1890 he was sentenced to two years in prison for attempting to molest a fourteen-year-old girl. A repeat offense in 1895, this time involving a toddler, caused him to be committed to the Waldau Mental Asylum in Bern. Then thirty-one years old, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

From the beginning of his hospitalization (which lasted until his death in 1930), Wölfli showed a facility for writing. At first, however, he was too agitated to engage in creative activity. But as his mood stabilized, he turned increasingly to drawing, and art in turn helped calm him. While it is thought that Wölfli first began drawing in 1899, his earliest surviving works date to 1904. Three years later, in 1907, a young psychiatrist named Walter Morgenthaler joined the Waldau staff. Morgenthaler, who worked at the hospital intermittently through 1919, encouraged Wölfli’s artistic efforts and documented them in a groundbreaking 1921 book, A Mental Patient as Artist. It was the first time that a mental patient had been called an artist or identified by name.

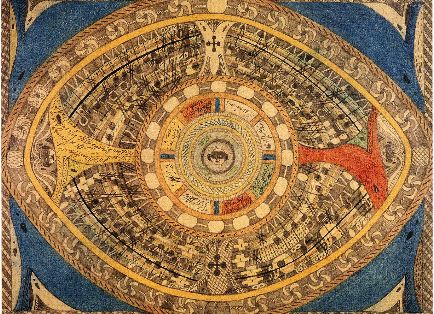

Wölfli’s earliest drawings, done between 1904 and 1907, already display his characteristic style and motifs: intricately nested geometrical forms, woven into mandala-like rounds or bound together with decorative bands, and occasionally interlarded with recognizable figural elements such as faces, snails and birds. Wölfli routinely used 39 ¼” x 29 ½” newsprint sheets, which might be pasted together in groups of two or four to create longer horizontals. His medium at this time consisted principally of graphite. It is said that he went through a pencil each week.

In 1908, possibly owing in part to Morgenthaler’s support, the scope of Wölfli’s work increased exponentially. The artist began using brightly colored pencils and embarked on an ambitious narrative project that eventually filled forty-five large volumes and sixteen school notebooks; 25,000 pages in all. Titled and numbered sequentially, these volumes comprise five segments: “From the Cradle to the Grave” (1908-12), “Geographic and Algebraic Books” (1912-16), “Books with Songs and Dances” (1917-22), “Album Books with Dances and Marches” (1924-25, 1927-28) and “Funeral March” (1928-30). Far from the rantings of a madman, Wölfli’s narrative evidences considerable advance planning and sustains a remarkable degree of coherence across its many pages. Images combine with mathematical, musical and phonetic notations to establish rhythms that give the whole a quasi-symphonic structure. However the work, with its arcane symbolism and idiosyncratic use of Swiss-German dialect, is not easy to decode. It is largely thanks to the efforts, over three decades, of the late art historian Elka Spoerri that we can now at least partially comprehend Wölfli’s monumental achievement.

The first segment of Wölfli’s narrative, “From the Cradle to the Grave,” is a fictionalized autobiography that recounts the various ordeals and adventures of the child Doufi (a nickname for Adolf). Inspired by an illustrated travel magazine, Über Land und Meer (Of Land and Sea), Wölfli sends his alter-ego and a band of companions across the globe and eventually into the cosmos. In the “Geographic and Algebraic Books,” the travelers encounter God-Father. Doufi, having amassed a considerable fortune, attempts to remake and perfect the world, replacing its mortal rulers with gods. This culminates in the establishment of the “St. Adolf Giant Creation” and Doufi’s rebirth as “St. Adolf II.” Here the story more or less ends. The “Books with Songs and Dances” and “Album Books with Dances and Marches” are compendia of songs, polkas, mazurkas and marches celebrating the St. Adolf Giant Creation. The cycle concludes with the “Funeral March,” a grand pseudo-musical composition built on rhyming the vowels, A, E, I, O, U, and illustrated chiefly with collage.

Wölfli’s narrative works remained in the Waldau Mental Asylum until their transfer, in 1973, to the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern. His international reputation was thus based less on these relatively inaccessible bound volumes than on the single sheets that the artist created, between 1916 and 1930, in exchange for art supplies and tobacco. Unlike the book drawings, which were usually done on newsprint, this so-called bread art was done on high-quality drawing paper. Though independent of the narrative work, the bread art echoes similar themes. Usually Wölfli wrote long explanations on the versos. Demand for the single sheets increased after the publication of Morgenthaler’s book in 1921, slowing Wölfli’s work on the final installments of his narrative. Nevertheless, the artist considered the narrative volumes his most important creation. Not only is the narrative a monumental achievement in its own right, but it establishes a framework for the single sheets, making it possible to understand Wölfli’s oeuvre as a cohesive alternative universe.