Josef Karl Rädler was born in Bohemia and at age 23, established a porcelain workshop in Vienna. There he led an apparently conventional life, married, and had four children. In his 40s, however, Rädler began to experience profound mood swings. In his manic phases, he launched fantastic business schemes, racked up huge expenses and became entangled in fruitless lawsuits. His family, feeling unable to deal with him, had him committed to the Viennese asylum at Pilgerhain in 1893. Rädler was subsequently diagnosed as suffering from “secondary dementia” (roughly akin to what we today call schizophrenia), but it has more recently been suggested that his symptoms could have resulted from temporal lobe disturbances caused by latent epilepsy.

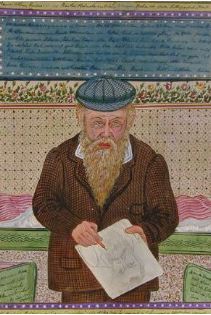

Although he had engaged in image-making through his profession, it seems Rädler did not start painting until 1897. His watercolors are all meticulously worked over on both sides of the sheet. One side usually centers on a relatively realistic image, while the other is covered with intricately nested skeins of symbolic figures and words that frequently taper off into illegible scribbles. In 1905, Rädler was transferred to a new state-of-the-art sanatorium at Mauer-Öhling, which featured large, park-like grounds, even including an amusement area where inmates could meet for folk festivals, dancing, bowling, and the like. The range of Rädler’s subject matter increased markedly with the scenery. While he formerly had painted mainly birds, he now made portraits of patients, scenes depicting them at their various activities, and renderings of the landscape surrounding the hospital.

Rädler spent most of his time painting and writing, consuming enormous quantities of paper and paint. It appears this activity was permitted, if not encouraged, because it kept him from causing trouble. He could be nasty and belligerent, and when not writing, he often harangued his fellow inmates with long philosophical discourses. His doctors viewed his artistic ambitions as further evidence of delusional megalomania. Hospital records describe Rädler’s pictures as “mannered, wooden, spiritless.” From our present-day perspective, however, one may well wonder whether the artist was branded a madman at least in part because he overstepped the boundaries of his prescribed social station. Had Rädler come from a more privileged background, he might have been welcomed into the then nascent avant-garde, or at least been shielded from confinement in a mental hospital.

—

After his death in 1917, Rädler’s work was abandoned for many years in a storeroom at Mauer-Öhling. When these drawings (numbering in the hundreds) were discarded in the mid-1960s, they were fortunately saved by the husband of Liselotte Traxler, one of the nurses. Traxler shared the find with the psychiatrist Dr. Leo Navratil (founder of the Haus der Künstler at the Lower Austrian Psychiatric Hospital), whose subsequent efforts to spotlight Rädler’s achievements brought the artist posthumous recognition outside the sanatorium. The Galerie St. Etienne introduced Rädler to the United States in 2001.